The morning arrived with all the nervous energy that comes with first-time moments. A job interview — not just any interview, but his very first one. The kind of milestone that marks transition from dreaming about independence to actually pursuing it.

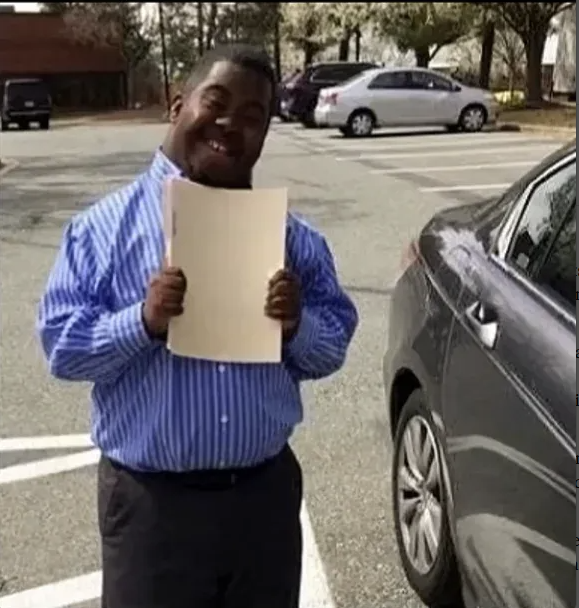

The neighbor’s son prepared carefully. He chose his clothes with intention, wearing a crisp blue striped shirt that suggested professionalism and care. He gathered whatever documents the interview required, holding them in hands that probably trembled slightly with anticipation. He practiced answers to questions he imagined they might ask.

He has Down syndrome. In a world that often sees disability before seeing the person, that sees limitation before seeing potential, he was walking into a space where he’d be judged on his abilities, his attitude, his fitness for employment.

But he carries something that many people — regardless of chromosome count — never fully develop: an unshakeable sense of self-worth. A refusal to let external limitations define internal reality.

His philosophy is simple and profound: “I have downs but downs don’t have me.”

He’s right in ways that extend far beyond his own circumstances. He recognizes that while Down syndrome is part of his biology, it doesn’t constitute his entire identity. It affects certain aspects of how he moves through the world, but it doesn’t determine his worth, his right to employment, his capacity for growth, or his ability to contribute meaningfully to a workplace.

The photograph captures him in the parking lot after the interview, holding his papers, wearing a smile that radiates pure joy. Not the nervous smile of someone hoping they performed adequately, but the genuine happiness of someone who just proved something to himself — that he could show up, represent himself well, and be taken seriously as a candidate.

His neighbor wrote about him with evident pride: “He is a happy person who has grown so much I’m so proud of him.”

That growth matters. Not just the development of job skills or interview techniques, but the internal growth that comes from refusing to accept society’s lowered expectations. The courage required to pursue employment when many people with Down syndrome face unemployment rates above seventy percent. The confidence needed to believe that he deserves a good job and a better life despite living in a world that often tells people with disabilities they should be grateful for whatever accommodations they receive.

Everyone deserves a good job and a better life. Not as charity or special consideration, but as basic human right. Employment offers more than income — it provides purpose, structure, social connection, and the dignity that comes from contributing to something larger than yourself.

Employers who hire people with disabilities often discover what this young man already knows: that capability takes many forms, that reliability and positive attitude matter as much as technical skills, that diversity in the workplace enriches everyone involved.

His smile in that parking lot tells a story that transcends this single interview. It’s the smile of someone who refused to let diagnosis become destiny, who insisted on being seen as a person first and a person with Down syndrome second, who understood that the only way to change how the world sees you is to change how you see yourself.

Whether he got that particular job or not, he’d already won something more valuable: proof that he could compete, that he belonged in professional spaces, that his philosophy — “I have downs but downs don’t have me” — wasn’t just words but lived truth.

He is right. Everyone deserves a good job and a better life. And sometimes, claiming what you deserve starts with showing up to the interview, holding your papers, and smiling because you know your worth regardless of what anyone else decides.