Tanzania, 1960. Young Jane Goodall sat quietly in the forest, watching chimps flee at her approach. Day after day, she tried to observe them, study them, understand them. But they saw her as a threat—a strange creature invading their world. Months passed with little progress. Just her, the trees, and animals who wanted nothing to do with her presence.

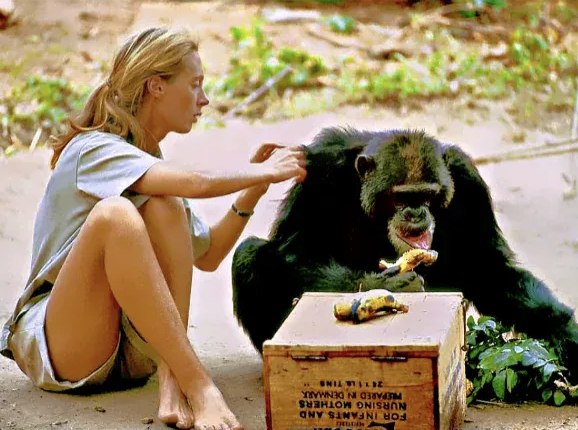

Then one stayed. David Greybeard. He didn’t run. He approached cautiously, took a banana from her hand, their fingers touching briefly in what would become one of the most significant moments in scientific history. First contact between human and wild chimpanzee built on trust rather than fear.

Days later, she found him using grass to fish termites from a mound. She watched, stunned, as he carefully selected stems, stripped them, inserted them into the termite nest, and pulled them out covered with insects. Tool use. Problem-solving. Behavior science had declared uniquely human.

Jane sent word of her discovery. The scientific establishment responded with skepticism bordering on dismissal: “Only humans use tools.” David Greybeard had just proved them catastrophically wrong. Jane’s funding doubled. Her career was saved. And the entire understanding of what separates humans from other species had to be rewritten.

For fourteen years, they sat together. The chimp who trusted first and the woman who listened. David would allow her near when other chimps wouldn’t. He’d share food, tolerate her presence, go about his life while she documented behaviors no one had seen before. Their relationship became the foundation of modern primatology—proof that with patience and respect, humans could understand our closest genetic relatives in ways previously thought impossible.

David died in 1968. Jane kept studying for fifty-seven more years. She expanded Goodall’s work across continents, trained generations of researchers, revolutionized conservation science, and became one of the most respected voices in environmental protection. All because one chimp decided to trust her, and she honored that trust by dedicating her entire life to understanding and protecting his species.

Last week, at age ninety-one, Jane Goodall passed away while editing conservation notes. Working until the very end, still fighting for the animals who’d given her life’s purpose. Her assistant found Mr. H beside her pillow—a stuffed monkey she’d carried to sixty-five countries, her constant companion through decades of travel, research, and advocacy. One hand still reaching across species, even in death.

The photo captures them early on—Jane and David sitting together beside a wooden crate, sharing a moment that would change science forever. A young woman barely into her twenties and a wild chimpanzee who decided she was worth trusting. Their fingers had touched over a banana, bridging a gap science said couldn’t be crossed.

David proved tools weren’t uniquely human. Jane proved that understanding between species requires nothing more complicated than patience, respect, and the willingness to listen. Together, they showed the world that the line separating us from other animals is far thinner than we’d believed—and that recognizing our kinship with other species makes us more human, not less.

Fifty-seven years after David died, Jane was still working. Still advocating. Still carrying Mr. H to remind her of the chimp who trusted first. Still reaching across species with the same hand that once touched David’s fingers over a banana in a Tanzanian forest.

One hand still reaching. One legacy still growing. One truth still echoing: that connection between species begins with trust, and when we honor that trust, we discover things that change everything we thought we knew.