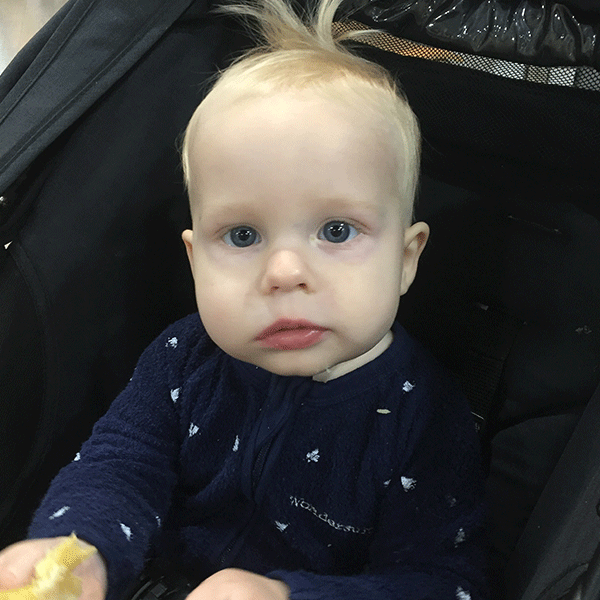

Ryder was just ten months old when everything changed for his family — the kind of change that rips the ground out from beneath your feet.

He was starting to crawl, his big sister Charlie giggling nearby. His mum, Kelly, was preparing to go back to work after maternity leave. The little family was stepping out of lockdown, enjoying the small things: fresh air, walks, hugs with relatives. Life felt simple. Life felt safe.

Then Ryder started getting sick. A cough here, more tiredness there. Kelly chalked it up to teething or baby colds. But then his face drooped. One of his eyes wouldn’t close when he cried. His parents recorded videos, hoping doctors would see what they saw — something wrong. When they finally went in, they were told not to leave the hospital without a scan. The words hung in the air: “your baby may have a tumour.”

At the hospital, after an MRI, the verdict came: Ryder had a tumour in his brain. Not just any tumour — an atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumour (AT/RT), one of the most aggressive childhood brain cancers. Genetic testing revealed it wasn’t just chance — Ryder had a mutation that made the tumour likely. Kelly’s heart broke. Her sister had died from childhood brain cancer when Kelly herself was just a kid. Now fate seemed to echo across generations.

The tumour’s location was cruel: interlaced with vital nerves, close to the brainstem. Surgeons couldn’t remove it all without risking permanent damage. They removed what they safely could, but they warned of consequences. Vocal cord palsy came first — Ryder could no longer swallow properly and needed a feeding tube for nearly two years. He lost slices of what most take for granted: speech, feeding, fluids, sleep without machines.

Chemotherapy started, intense and unrelenting. Hospital stays stretched for weeks. Radiotherapy under anesthesia, five days a week for six weeks, despite Ryder’s tiny age. Each treatment was a hammer blow. Kelly and Alan would stay at Ronald McDonald House, watching cycles of hope crash into cycles of despair, then rebuild again. Big sister Charlie hardly knew her brother was sick — they were separated often, each in different worlds of fear and healing.

Evenings were the hardest. Kelly would sit by Ryder’s bed with his hand in hers, whispering stories. Alan would catch glimpses of tears, quickly wiped away. Every scan was a cliff’s edge — relief if it showed tumour shrinkage, dread if not.

And then, amidst the darkness, came light.

After many rounds of chemotherapy and the crushing weight of radiation, scans began to show something miraculous: the tumour was shrinking. Shrinking enough that surgeons took a second look. They operated again — carefully removing the parts left, and found what they removed was already dead tissue.

They didn’t stop there. Ryder was started on a trial drug called Tazometostat, a targeted therapy aimed to stop the cancer from creeping back. He was on it for twelve months. It was a gamble. But what is life if not a collection of brave gambles?

Today, Ryder is full of energy. No facial palsy. No visible damage from treatment’s fury. He still goes for scans — kidneys closely watched, because AT/RT’s genetic footprint can cast shadows elsewhere. But he runs, laughs, plays. He’s a toddler who doesn’t know his worst days. He simply knows now: “I am”.

Kelly tells friends: “We take it three months at a time.” And yet each three-month mark is a badge of victory. Charlie gets hugs from her brother; Alan and Kelly breathe just a bit easier.