For over 43 years, Mohammed Aziz has been Rabat’s devoted bookseller. More than four decades in the same place, serving the same community, surrounded by the same passion—books. In a world where businesses come and go, where people change careers multiple times, where consistency is increasingly rare, Mohammed has spent 43 years doing exactly what he loves in exactly the same place.

At 72, he still spends six to eight hours daily reading, having consumed more than 5,000 books in his lifetime. This isn’t someone who sells books without reading them, who treats literature as mere product to move. Mohammed is a reader first, a bookseller second. Six to eight hours daily at age 72—that’s dedication that goes far beyond professional obligation. That’s genuine love of reading, sustained across decades.

More than 5,000 books consumed in a lifetime means averaging well over 100 books per year for 43 years. That’s not casual reading—that’s voracious, sustained intellectual engagement. Mohammed isn’t just knowledgeable about books; he’s lived inside them, absorbed thousands of stories and ideas and perspectives, become the kind of person who can recommend exactly the right book because he’s read everything.

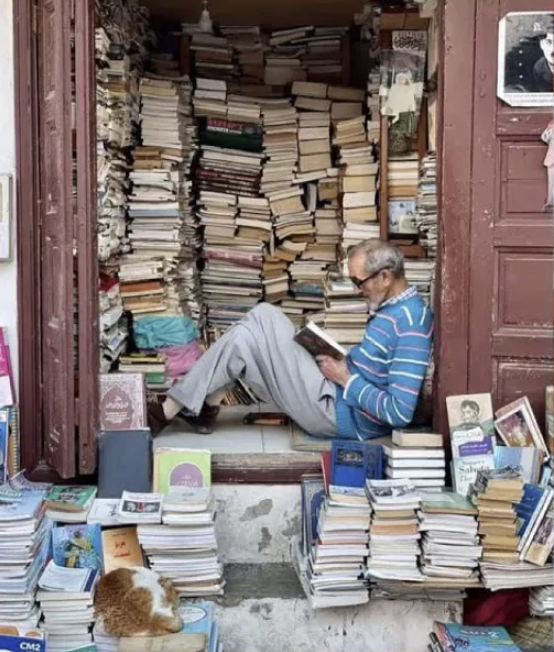

But what surprises visitors most is his practice of leaving books completely unattended on the street, vulnerable to theft. The photograph shows exactly this—books stacked everywhere, piled on the ground outside the shop, covering every surface, extending onto the sidewalk. Mohammed sits among them reading, but he’s not watching them. There’s no security, no locked cases, no careful inventory control. Just books, accessible to anyone, trusted completely to strangers who could easily steal them.

When asked why he trusts strangers so completely, Mohammed shares a timeless Arabic proverb: “The reader does not steal, and the thief does not read.” Seven words that contain an entire philosophy about human nature, about books, about who is drawn to literature and why theft isn’t actually the concern it might seem.

The reader does not steal. People who love books, who value reading, who are drawn to literature—they don’t steal. Not because they’re morally superior in all ways, but because their relationship with books is based on respect. You don’t steal what you genuinely value. Readers understand that books are meant to be shared, protected, passed on. Taking one without paying violates the entire relationship between reader and book.

And the thief does not read. People who steal are looking for quick value, for things easily converted to money or immediate use. Books—especially used books in Arabic from a street vendor in Rabat—don’t fit that profile. They’re heavy, they’re hard to resell, they require literacy and interest to have value. Thieves looking for easy targets skip right past Mohammed’s unguarded books because they’re not what thieves are looking for.

So Mohammed leaves his books on the street, trusting that proverb to be true, and apparently it is. For 43 years, he’s operated this way—books piled everywhere, accessible to anyone, trusted to a community that could steal them but doesn’t. Either because readers are the ones who visit his shop and readers don’t steal, or because thieves ignore books as not worth their effort.

The photograph captures this beautifully. Mohammed sits in his doorway wearing a striped sweater, reading a book, surrounded by towers of books stacked inside and outside his shop. The stacks are precarious, built up to shoulder height and beyond, covering every available surface. Books sprawl onto the sidewalk, sit unprotected on the ground, create a maze that visitors must navigate to reach him.

And he’s just sitting there reading, not watching the books, not worried about theft, completely absorbed in whatever text he’s currently consuming. At 72, after 43 years, still spending six to eight hours daily reading, having consumed more than 5,000 books, trusting strangers completely with his unguarded inventory.

This is what passion looks like when sustained across decades. Mohammed isn’t operating a business in the typical sense—he’s created a life around books, a space where reading is the primary activity and selling happens almost incidentally. People who visit his shop in Rabat encounter not a salesman but a fellow reader, someone who can discuss what they’re looking for, recommend based on genuine knowledge, share the love of literature that has defined his 72 years.

The Arabic proverb he quotes—”The reader does not steal, and the thief does not read”—has proven true for 43 years. Mohammed’s trust in strangers, his willingness to leave books completely vulnerable to theft, hasn’t resulted in his inventory disappearing. Instead, it’s created a space where books are accessible, where browsing is easy, where the relationship between bookseller and customer is based on shared love of reading rather than suspicion and security.

Visitors are surprised by the unattended books on the street because we’re conditioned to expect security measures, to assume that unguarded merchandise will be stolen. But Mohammed understands something about books and readers that retail security misses—that people who care enough about books to visit a second-hand bookshop in Rabat aren’t going to steal them. That the overlap between “people interested in Arabic literature” and “people who steal from small vendors” is essentially zero.

For over 43 years, this trust has sustained his business. At 72, still reading six to eight hours daily, having consumed more than 5,000 books, Mohammed Aziz continues to be Rabat’s devoted bookseller—sitting among precarious towers of unguarded books, trusting strangers completely, proving every day that the reader does not steal and the thief does not read.