Ten-year-old Lucas’s severe stutter made school torture. Not just mild speech difficulty but a stutter so severe that speaking in class became an ordeal of fear and humiliation. The kind of stutter that makes other children uncomfortable, that leads to giggles and whispers, that transforms simple acts like answering questions or reading aloud into moments of panic.

Called to read aloud, he’d freeze while classmates giggled, until he stopped talking completely. The pattern that developed from repeated trauma—teacher calls on Lucas, Lucas tries to speak, the stutter prevents words from coming out smoothly, classmates laugh or whisper, Lucas freezes in humiliation. Repeated enough times, this cycle led to complete shutdown—Lucas stopped trying to speak at all in class, choosing silence over the certainty of stuttering and mockery.

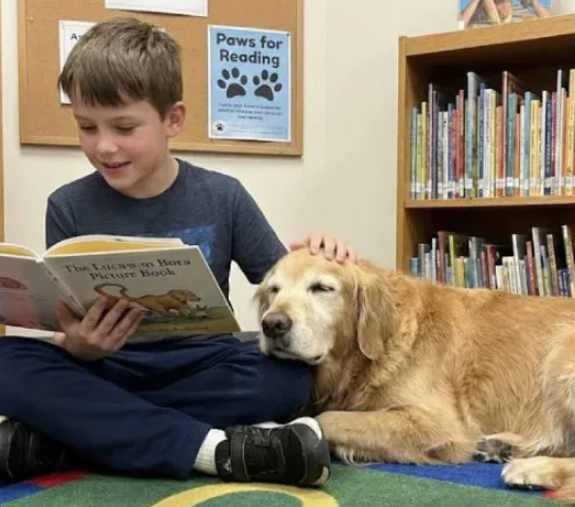

His mother enrolled him in library program “Paws for Reading.” A therapeutic reading program where children read aloud to trained therapy dogs instead of humans. The premise is simple but profound—dogs don’t judge, don’t laugh, don’t show impatience when words come slowly or with difficulty. They just listen, providing the safe, nonjudgmental audience that struggling readers need to practice without fear.

Golden Retriever Barnaby rested his heavy head on Lucas’s knee, listening without judgment. The physical setup of their sessions—Lucas sitting with a book, Barnaby lying beside him with his head resting on Lucas’s knee, creating physical connection and comfort. Barnaby didn’t care if words came out smoothly or with struggle. Didn’t react to stuttering with laughter or impatience. Just listened, steady and calm, providing the acceptance Lucas desperately needed.

Weekly sessions built Lucas’s confidence. Consistency over time—not a one-time intervention but regular sessions where Lucas practiced reading aloud in a safe environment. Each week, reading to Barnaby, experiencing success without judgment, slowly rebuilding confidence that had been destroyed by years of classroom humiliation. The practice itself mattered, but more importantly, the emotional safety of practicing with a listener who accepted him completely regardless of how his speech sounded.

Three months later, he volunteered to read a poem before his class. The transformation—from a boy who’d stopped talking completely to avoid humiliation to a boy confident enough to voluntarily read aloud in front of the classmates who’d mocked him. Three months of weekly sessions with Barnaby had rebuilt enough confidence that Lucas was willing to risk speaking in the setting that had traumatized him.

He stumbled but finished strong. The performance wasn’t perfect—Lucas still stuttered, still struggled with some words. But he didn’t freeze, didn’t give up, didn’t let the difficulty stop him. He pushed through the stumbles and finished reading the poem, completing what he’d set out to do despite the challenge.

The teacher cried. Classmates applauded. The emotional response from adults and children who understood the magnitude of what Lucas had just accomplished. His teacher cried recognizing the courage it took for Lucas to volunteer and the progress he’d made. Classmates applauded—not mockingly but genuinely, supporting him, celebrating his achievement, responding with encouragement rather than the cruelty they’d shown before.

Lucas learned that sometimes the best listeners are those who can’t speak a word. The profound lesson embedded in his experience—that Barnaby, who couldn’t speak at all, was a better listener than any human had been. That the silent, nonjudgmental presence of a dog who simply accepted him provided exactly what Lucas needed to rebuild confidence and find his voice again.

The photograph shows Lucas sitting on the floor in a library, reading a book to Barnaby the Golden Retriever who lies beside him. Behind them, a “Paws for Reading” poster is visible on the wall, and bookshelves full of children’s books line the walls. Lucas is focused on his book, Barnaby is relaxed and attentive, and everything about the image speaks to the safe, comfortable environment these sessions create.

Severe stuttering in children creates cascading problems beyond the speech difficulty itself. The stutter leads to anxiety about speaking, which often makes the stutter worse. Negative reactions from peers create shame and avoidance. Repeated humiliation in classroom settings can lead to selective mutism—choosing not to speak at all rather than face the certainty of stuttering and mockery.

Lucas had reached that point—stopped talking completely in class. Not because he couldn’t speak at all, but because the social cost of stuttering had become unbearable. Silence felt safer than attempting speech and facing the laughter and whispers that followed.

Paws for Reading and similar programs understand that the psychological barriers to fluent reading often matter more than the technical skills. Children who struggle with reading—whether due to stuttering, dyslexia, or other challenges—often develop such intense anxiety about reading aloud that they avoid practice entirely, which makes improvement impossible. The anxiety creates a vicious cycle: fear of reading prevents practice, lack of practice prevents improvement, lack of improvement reinforces fear.

Therapy dogs break this cycle by providing completely nonjudgmental listeners. Barnaby didn’t care if Lucas stuttered. Didn’t show impatience when words came slowly. Didn’t laugh or whisper to other dogs about Lucas’s difficulties. Just listened, accepting whatever Lucas could produce, providing the safe environment where practice could happen without fear.

Barnaby rested his heavy head on Lucas’s knee—the physical contact matters. The warm, steady weight of a dog’s head provides comfort and grounding. The connection reminds Lucas he’s not alone, that Barnaby is present and attentive, that this is a shared experience rather than a performance being judged.

Weekly sessions built confidence through repetition and success. Each week, Lucas experienced successful reading—maybe not fluent or smooth, but successful in the sense that he read to a listener who accepted him completely. Those repeated experiences of success slowly rebuilt the confidence that had been destroyed by years of classroom failure and humiliation.

Three months later, Lucas volunteered to read a poem. The timeline shows this wasn’t instant transformation but gradual progress. Three months of weekly sessions, of reading to Barnaby, of experiencing acceptance, of slowly believing that maybe he could speak in front of others without disaster. Until finally, he felt confident enough to try again in the classroom setting that had traumatized him.

He stumbled but finished strong. Acknowledging the reality—Lucas still has a stutter, the reading wasn’t perfectly fluent. But he didn’t let the stumbles stop him. He pushed through, finished what he’d started, demonstrated courage and determination that matter more than fluency.

The teacher cried, understanding the magnitude of Lucas’s achievement. Having watched him shut down completely, stop talking, avoid all classroom participation—seeing him volunteer to read aloud and then actually complete it was overwhelming evidence of transformation.

Classmates applauded, responding differently than they had before. Maybe they’d matured slightly in three months. Maybe Lucas’s courage inspired them. Maybe the teacher had talked to them about supporting classmates who struggle. Whatever the reason, instead of giggles and whispers, Lucas received genuine applause and support.

Lucas learned that sometimes the best listeners are those who can’t speak a word. Barnaby, who couldn’t offer verbal encouragement or advice, who couldn’t speak at all, turned out to be exactly the listener Lucas needed. The silent, nonjudgmental acceptance of a dog who just listened provided what years of human interaction hadn’t—the safe space to practice, fail, struggle, and gradually improve without fear of mockery or rejection.