They were the silent laborers of the coal mines. Not celebrated, not remembered in most histories, barely acknowledged in the stories we tell about industrialization and the coal that powered the modern world. Just horses—thousands of them, maybe hundreds of thousands over the decades—who worked underground in conditions that would horrify anyone who stopped to think about what their lives entailed.

Born underground, these horses endured a life without sunlight or fresh air. Some were literally born in the mines, never seeing daylight, never experiencing life above ground. Others were brought down as young horses and never returned to the surface. Either way, they lived their entire existences in darkness, in the artificial light of mining lamps, in air thick with coal dust.

Pulling heavy wagons through suffocating darkness, they lived and perished in the tunnels. Their work was essential to mining operations—pulling carts full of coal from working faces to collection points, transporting equipment and supplies through narrow tunnels where machines couldn’t navigate, providing the motive power that kept mines productive before full mechanization.

The darkness was complete when lamps weren’t present. The air was bad—full of coal dust that damaged lungs, low in oxygen in poorly ventilated sections, sometimes containing dangerous gases that killed humans and horses alike. The space was confined, the tunnels barely tall enough for horses to move through, the work constant and exhausting.

These “ghosts” sacrificed their entire existence to power the world above. Called “pit ponies” or “mining horses,” they were treated as equipment more than as living beings. Bought for their strength and size, worked until they died or became too injured to continue, replaced when they failed. Their sacrifice powered industries, heated homes, enabled the industrial revolution—all while they lived and died in darkness beneath the ground.

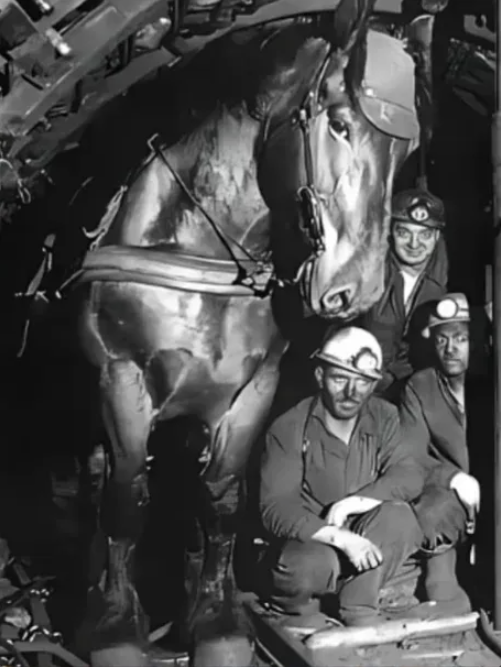

The photograph shows a stark underground scene—miners with their helmet lamps standing beside horses harnessed for work in what appears to be a coal mine tunnel. The horses look thin, their coats probably dull from lack of sunlight and poor nutrition, their eyes adapted to darkness. The miners look at the camera, their faces showing the hard reality of underground work, their presence beside these horses suggesting the interdependence of human and animal labor in this brutal environment.

Born underground means never experiencing normal horse life. Never running in pastures, never seeing sun or stars, never grazing on grass, never experiencing weather or seasons or the basic elements that constitute horses’ natural environment. Just tunnels, darkness, work, and coal dust from birth to death.

A life without sunlight or fresh air means constant physical suffering. Horses need exercise, space, good air, proper light. Underground, they got none of those things. Respiratory diseases were common, their lungs damaged by constant coal dust exposure. Injuries were frequent in narrow tunnels where one misstep could mean collision with tunnel walls or equipment. Nutrition was inadequate—hay and grain brought underground, never the varied vegetation horses naturally eat.

Pulling heavy wagons through suffocating darkness was exhausting, dangerous work. The wagons were loaded with hundreds of pounds of coal. The tunnels were uneven, sometimes muddy or flooded, always dark. The work was repetitive—the same routes over and over, the same heavy pulling, the same darkness and dust, day after day without variation or relief.

They lived and perished in the tunnels. Some worked for years before dying from injury, disease, or exhaustion. Others died young from accidents or adverse conditions. When they died, their bodies were often left underground—too difficult or expensive to bring large dead animals to the surface. They literally perished in the tunnels where they’d lived, their bones remaining underground as anonymous testament to their labor.

These “ghosts” sacrificed their entire existence. Called ghosts because they lived unseen by the world above, because they haunted the darkness of mines without recognition or acknowledgment, because their sacrifice was invisible to the people who benefited from it. Coal heated homes and powered factories and enabled industrial development, but the horses who made that coal accessible remained unknown and unacknowledged.

To power the world above—that’s what they were sacrificed for. The comfortable homes, the industrial products, the economic development, all the benefits that coal provided were built partly on the invisible suffering of these animals. They powered the world from below, from darkness, from conditions that we’d now recognize as severe animal cruelty but that were simply standard practice in that era.

Modern mining eliminated pit ponies decades ago. Mechanization, improved transportation technology, and eventually awareness of animal welfare ended the practice of using horses underground. The last pit ponies in Britain were retired in the 1990s, some living out final years in sanctuaries where they experienced sunlight and pastures for the first time.

But for over a century, they were essential to mining operations. Invisible but necessary. Suffering but productive. Sacrificing their entire existences—health, comfort, natural behaviors, everything that makes life worth living for horses—to extract coal that powered the industrial world.

This photograph serves as their memorial. Evidence that they existed, that their labor mattered, that the comfortable world above was built partly through their suffering. The miners beside them probably felt some affection for these horses—you work alongside any being daily and relationships form. But affection didn’t change the fundamental brutality of the horses’ existence.

Born underground, living without sunlight or fresh air, pulling heavy wagons through suffocating darkness, perishing in the tunnels where they’d spent their entire lives—this was the reality for thousands of horses over decades of industrialization. Silent laborers whose sacrifice powered the world above, whose suffering enabled progress and development, whose existence was so invisible that most people never knew they were there.

They were ghosts. And this photograph preserves their memory, reminds us that progress often has hidden costs, that the comfortable world we inherited was built through sacrifices we rarely acknowledge. These horses—these silent laborers of the coal mines—powered the world from suffocating darkness, and we owe them at least the recognition that their existence mattered, their suffering was real, and their sacrifice helped build the modern world.